Why Do We Sometimes Love Being Scared?

Some of us really love giving ourselves a good scare. Some of us watch horror movies, others like having a good scream on a rollercoaster. So how does this work exactly? Fear is supposed to be uncomfortable, not enjoyable… isn’t it? Let’s find out what’s going on here!

The Biology of Fear

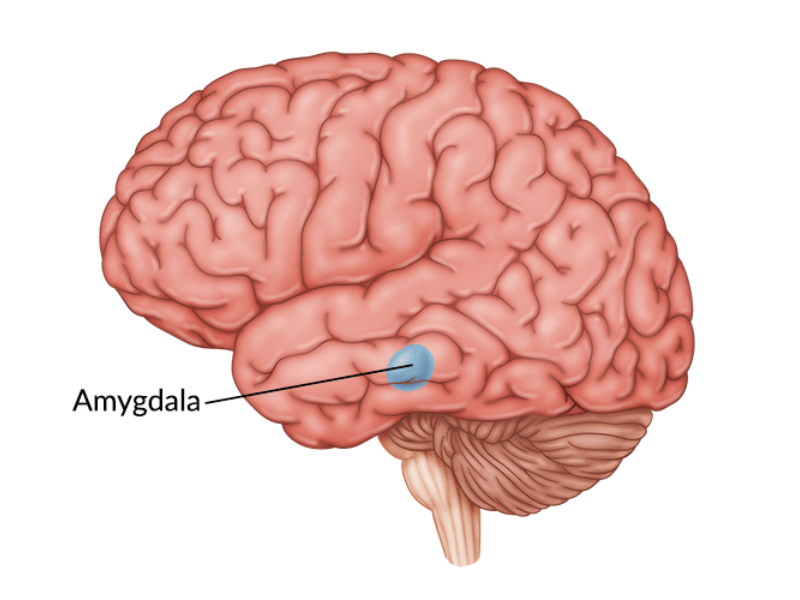

Fear is a deeply embedded evolutionary mechanism. Its role is to help living things protect themselves against threats in their environment. In the brain of mammals, fear starts in the amygdala... and that includes the human brain! The amygdala is a special nest of neurons in the brain.

The amygdala’s job is to be on the lookout for anything unusual, including things that might be a threat. When it detects something, it sends signals to the parts of the brain that prepare our bodies to respond.

The Body’s Response to Fear

The body responds to fear in a number of ways: the brain goes on high alert, our pupils dilate, our breathing gets faster, our heart beats faster, and our blood moves faster. Vital organs are pumped full of oxygen and nutrients and our muscles are flooded with extra energy, known as glucose. All these physiological changes focus our attention on the here and now and get us ready to jump into action in the blink of an eye.

The brain doesn’t stop there, though. It keeps monitoring the situation. The part of the brain that stores our memories, called the hippocampus, also kicks in to analyze the amygdala’s danger signal. It looks at what’s really happening using our knowledge of the world and our past experiences as its guide. The hippocampus asks: “Is there really a threat here, or is this a false alarm?” This is how the brain rationalizes our body’s fear instinct and saves us from spinning into a panic.

The Thrill of Fear

Feeling fear also pumps our body full of hormones, like adrenalin, dopamine, and endorphins. These are all designed to help our bodies react and move very quickly in the face of fear, but they also offer us a sense of power and calm. Think about how you can talk yourself down from fear or find a sense of control over whatever is scaring you, like when you watch a horror movie and know you can press pause at any time. This ability to rationalize what is scaring us is what lets us enjoy all those feel-good hormones without the panic of real fear.

In fact, experiencing fear in small, short-lived doses can be quite invigorating! It can distract us from our everyday worries and jolt us into experiencing the moment fully and completely, if only for a short while.

If sensing threats is the starting gun for our fear response, encountering the unknown when faced with new and unusual situations generates a similar response. This explains why many people make it a point to seek out all sorts of new thrills and chills; to get the boost of energy that the fear response provides. For some, it can even be a bit addictive!

Finding the Right Dose

Not everyone handles fear the same way. Visiting a haunted house can be a bore for some, but it can be a real nightmare for others! The trick is to understand how much fear you can handle and knowing how much is fun... and how much is too much. Keeping our bodies in a state of fear over too long a time or at very intense levels can be harmful for us, physically and mentally.

This is not to say that we should completely avoid feeling fear. Experiencing fear now and again can be helpful! It can help us get better at managing our fear of the unknown and teach us how to manage ourselves when we are confronted with new and unexpected experiences. In fact, when young children learn, small doses of risk and fear can teach their brains and bodies how to better manage anxiety.

Halloween is all about getting candy and getting scared, but remember: both are best enjoyed in small doses!

Our Human exhibition features an interactive game that plays on our fear of the unknown. It dares visitors to put their hand inside a dark hole. Think you could do it?

Sources

Hosker-Field, A. M., Gauthier, N. Y., & Book, A. S. (2016). If not fear, then what? A preliminary examination of psychopathic traits and the Fear Enjoyment Hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 278‑282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.016

Javanbakht, A., & Saab, L. (2017 October 28). The science of fright: Why we love to be scared. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/the-science-of-fright-why-we-love-to-be-scared

Latham, K. (2022, October 23). Why we enjoy fear: The science of a good scare. The Observer. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2022/oct/23/why-we-enjoy-fear-the-science-of-a-good-scare

Lindberg, E. (2018 October 30). Why do we like to be scared? USC experts explain the science of fright. USC Today. https://today.usc.edu/why-do-we-like-to-be-scared-usc-experts-explain-the-science-of-fright/

Manning-Schaffel, V. (2017 October 23). Why do we like to be scared? NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/better/health/fondness-fear-why-do-we-be-scared-ncna812661